What is the Divine Council?

God's Divine Council - The Whole Counsel Blog

In the scriptures, when the hosts of angels, archangels, thrones, dominions, virtues, principalities, powers, cherubim and seraphim are described, they are described using predominately one of two metaphors. The first of these has already been used here in the previous sentence, that of the ‘heavenly hosts’. This reference to the multitude of angelic beings forms one of the names given to the God of Israel in the Old Testament, Yahweh Sabaoth. Because of the similarity in English transliteration, this title is often confused with a reference to the Sabbath. It is not, however, the Hebrew words ‘shabat’. Rather, it is the plural substantive form of the verb ‘tsavah’. This is the verb that is used in Genesis 1, for example, to describe the way in which the waters and the skies teemed with life brought forth by God. It is also used at the beginning of the book of Exodus to describe the way in which the Israelites had been fruitful and multiplied even in Egypt, and become many. Yahweh Sabaoth can best be translated into English as ‘Lord of Hosts’. This phrase is not merely pointing to the vast number of angelic beings, however, but to their array. This is properly speaking a military title for Israel’s God, and is most often used within military metaphors to describe the Lord as commander of armies and mighty in battle.

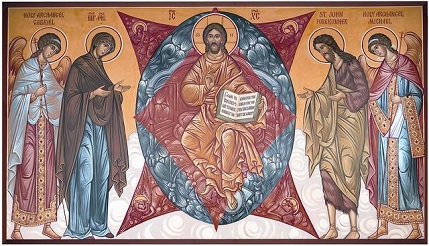

The second metaphor, which will be the focus of this post, and developed further in two subsequent posts, is on the other major metaphor, which is the description of the divine council. Simply put, the God of Israel is depicted as a king enthroned, ruling over his creation. The angelic beings then are part of his royal court, a divine council, over which he presides. This divine council is both directly depicted and alluded to throughout the Old Testament. In the New Testament, particularly centered around the incarnation and ascension of Jesus Christ, the nature of the divine council is transformed. Ultimately, it is through understanding the scripture’s teaching about the divine council that we will see the way in which the scriptures clearly teach the reign and intercession on our behalf of the saints in glory, as has been recognized in the Orthodox Church throughout the ages.

Two key terms used in describing God’s divine council recur whenever it is being discussed. The first is the reference to the mountain of God as the ‘mountain of assembly’, in Hebrew ‘har moed’. This is not a particular mountain where the God of Israel lived, ala Mt. Olympus in Greek mythology, but rather, as the angelic beings are part of the invisible creation, various mountains become the ‘mountain of assembly’, such as Sinai when God’s presence descends upon it, or Zion when it becomes the site of divine worship, or Tabor at the time of the Transfiguration of Christ. Importantly, in the book of Revelation, the ultimate battle between Christ and his enemies takes place at ‘armageddon’, a Greek transliteration of ‘har moed’. In whatever place God is, he is surrounded by his divine council and presides. It is for this reason that his throne is depicted as also serving as a chariot, as discussed in a previous post. The second important term is another title of the God of Israel, and that is ‘God Most High’ or ‘the Most High God’. As we will see, the pagan nations will come to worship some fallen members of the divine council as ‘gods’. Setting apart Yahweh as the ‘Most High’ is pointing to the fact that while there are other spiritual beings whom some call gods or worship as gods, none of them are like Yahweh, the God of Israel. It is not surprising then that the title ‘Most High’ is the one which we most often see spirits, both angelic and demonic, using to refer to God (cf. Mark 5:7, Luke 1:32, 35, 76, 8:28, Acts 16:17).

The rebellion of Satan, and his fall, takes place within the context of the divine council as it is described in Isaiah 14 and Ezekiel 28. Isaiah describes the first rebel’s intent, to set his throne on high, on the mount of assembly (14:13). He intends to make himself like the Most High (v. 14). Instead he is thrown down into Sheol, into the earth. He is the god of nothing but dust and ashes. Ezekiel’s description is in even greater detail. It describes Satan’s state before his fall, a beautiful creation of God walking in the garden of God, Eden (28:13). God had created him for, and had given him, a position near to his own throne (v. 14). Yet Satan became filled with arrogance over his own beauty and position (v. 17) and he committed evil, and therefore was thrown down from the heavens to the earth and ashes (v. 18). Ezekiel 28 is further connecting Satan to the figure of Baal, who was the primary deity worshipped in Tyre, against whom Ezekiel 28’s oracles are directed. Baal is a title, meaning ‘lord’ or ‘master’, which was applied to many different gods by Phoenicians and other Semitic people groups. There are therefore references in the Old Testament to Baals as a plural, or to the Baal of a particular place. Baal when used alone, and particularly in reference to the Phoenicians as here and in the life of Elijah refers to the god Hadad.. In the mythological Baal cycle, the arc of the story, which became the basis for the festivals and rituals of the Baal cult, the story is told of how Baal rose up amongst the gods of the high council of gods to achieve a throne over them all and a position of supremacy. Ezekiel 28, then, can be seen to both argue that the Baal cycle is a false version of the story of Satan’s fall in which he achieved his goal, and that worshippers of Baal are in fact worshipping Satan. This is why Ezekiel can speak of the devil having ‘sanctuaries’ (v. 18). It is also why Baal will be identified with the devil throughout later Jewish history (cf. Matt 10:25, 12:24,27, Mark 3:22, Luke 11:15, 18, 19). These descriptions of Satan’s fall from within the prophetic books are also important to our understanding of the curse of Genesis 3, which is not the story of how snakes ‘lost their legs’. The imagery of being cast to the ground and eating dirt and ashes matches the imagery used in these prophetic texts and represents, in both places, the dead who are seized and swallowed by Sheol or Hades. It is for this reason that in Christian iconography and art Hades is often depicted as an open-mouthed serpent, and it is this imagery that lies behind, for example, St. John Chrysostom’s poetic description of the resurrection of Christ.

Satan, however, is not the only angelic being who fell into sin. A group of angelic beings did so in the days of Noah (Gen 6:1-2, 1 Pet 3:19-20). Another group, like Satan became arrogant and sought to be worshipped as gods by the nations of the world. The tower of Babel, a ziggurat in the city of Babylon, was an attempt by human beings to create the mount of assembly through their own efforts, to draw God down from heaven and thereby seek to manipulate and control him. As punishment and to prevent further such evil, God scattered and disinherited the nations. He then immediately, in the narrative of Genesis, began with Abraham to create a nation for himself, through which ultimately he planned to reconcile all nations to himself in Christ. In regard to those other nations, however, Deuteronomy 32:8 reflects on what took place. God reckoned to the nations of the world (numbered in Genesis at 70) their inheritance, to all the sons of Adam, he set their boundaries according to a certain number. Most English translations at this point reflect the medieval Hebrew text and say, “according to the number of the sons of Israel”. In addition to making little to no sense in context, nowhere do the scriptures number the nations at 12. The Greek text of Deuteronomy from the Septuagint translates an earlier form of the Hebrew, stating that God divided them ‘according to the number of his angels’. Recently, among the Dead Sea scrolls, we have recovered what that Hebrew originally read, that they had been divided ‘according to the number of the sons of God’ (4QDeut). Deuteronomy is here saying that when he disinherited them, God assigned these nations to angelic beings in the divine council. These beings became corrupt, however, and were worshipped by the nations they were to govern. This is why ‘all the gods of the nations are demons’ (Deut 32:17, Ps 96:5, 1 Cor 10:20). This situation is also described in Daniel 10, as Daniel’s angelic visitor describes being delayed by a ‘Prince of Persia’, against whom he was aided by St. Michael the Archangel (v. 13), and that he is due for further battle alongside St. Michael against both this ‘Prince of Persia’ and the ‘Prince of Greece’ (v. 20-21). Psalm 82, then, describes the pronouncement of judgment made by God against these beings, that they shall perish. The final verse of this Psalm is sung in the Orthodox Church on Holy Saturday, to celebrate the victory of Christ over the dark powers and the beginning of God’s inheritance of all of the nations.

These rebellions did not destroy the divine council, as it continues to be described in scripture. And the role of the spiritual beings who are a part of the divine council is not purely a passive one. Deliberations take place within the council as depicted in scripture. The book of Job features a famous example of the ‘sons of God’ gathering to present themselves to God including ‘the Satan’. This is a throne room scene, and in it Job stands accused, and discussions regarding him take place (Job 1:6-12). A less well known example takes place in 1 Kings 22:19-23. God has decreed that Ahab will be brought down as King of Israel for his many egregious sins, but as the prophet speaks of this, he describes a meeting between the Lord seated upon his throne, and the heavenly hosts gathered about it on all sides, in which God puts the question to them as to who will persuade Ahab to go to Ramoth-Gilead where he will die (v. 20). There are various proposals from various angelic beings, until one spirit volunteers to go and speak through Ahab’s false prophets to promise him victory in this battle in which he will die (v. 22). This plan is accepted by God, and goes forward, though it is worth noting that a true prophet is then sent to Ahab to tell him all of this, and give him one final chance to repent. Within Second Temple Judaism, this participation of the angelic beings in God’s council was also seen in a positive light Particular angelic beings were seen to bring the prayers for mercy and the tears of God’s people before the throne of God and offer them to him. Requests were made to these angelic beings to represent a person’s cause before the Lord. Angels of mercy were requested to plead for mercy for God’s people. Before the shofar was blown on holy days, a prayer was said requesting the angels of the horn’s music to intercede before the throne of the Lord for atonement for the people. While it is God who reigns from the throne and shows mercy and kindness, God is seen, here in the Old Testament, to involve his angelic creations in his governance of his creation as a grace to them.

Humans in the Divine Council - The Whole Counsel Blog

In last week’s post,

God’s divine council, the angelic beings surrounding his throne with

whom He shares graciously his governance of the heavens and the earth,

was introduced. There are several ways in which human persons in the

Old Testament encounter and interact with the divine council. These

encounters and modes of interaction lay the groundwork for a transformed

relationship in the New Covenant, which will be the subject of next

week’s post. Simply put, every encounter with God the Father in the Old

Testament is mediated either through God the Son, as was discussed in a

previous series on this blog, or by angelic beings, as will be

discussed here.

In last week’s post,

God’s divine council, the angelic beings surrounding his throne with

whom He shares graciously his governance of the heavens and the earth,

was introduced. There are several ways in which human persons in the

Old Testament encounter and interact with the divine council. These

encounters and modes of interaction lay the groundwork for a transformed

relationship in the New Covenant, which will be the subject of next

week’s post. Simply put, every encounter with God the Father in the Old

Testament is mediated either through God the Son, as was discussed in a

previous series on this blog, or by angelic beings, as will be

discussed here.

Though these encounters are far from common, the most common mode of encounter between a human person and the divine council in the Old Testament is for a human person to be brought into a gathering of the council. The vision in which Isaiah receives his prophetic calling is recorded in Isaiah 6. Isaiah sees the Lord enthroned, ‘high and lifted up’. Closest to the throne are the seraphim, whom he beholds worshipping the Lord perpetually. When the Lord speaks, however, it is not to command Isaiah, rather it is to pose a deliberative question to the council gathering in which Isaiah is now present. The question, “Whom shall I send, and who will go for us?” is not dissimilar from the scene in 1 Kings/3 Kingdoms 22:19-20, where the question is posed to the council as to who will persuade Ahab. In that case, a spirit volunteered to go, in this case, Isaiah volunteers to bring the message of judgment to Israel.

Though it is not detailed as such in the Torah, Moses’ meetings with God atop Mt. Sinai is described by later Judaism, including in the New Testament, as entering into such a meeting. The New Testament repeatedly says that the Torah was given by, or through, angels. St. Stephen refers to the Judean authorities as those who have ‘received the law delivered by angels’ and not kept it (Acts 7:53). St. Paul, in Galatians, in describing the addition of the Torah to the Old Covenant, says that it was ‘delivered by angels in the hand of a mediator’, namely Moses (Gal 3:19). Hebrews describes the seriousness of the commandments of the Torah by pointing out that ‘the message declared by angels proved to be reliable, and ever transgression or disobedience received a just retribution’ (2:2). Beyond the New Testament, this was the common understanding of the giving of the Torah in Second Temple Judaism, as seen for example in Josephus, ‘We have learned the noblest of our doctrines and the holiest of laws from the angels sent by God’ (Antiquities xv:136).

Further, however, the Tabernacle in particular was constructed according to the pattern of the place of meeting which Moses beheld on the mountain (Heb 8:5). As seen in Isaiah’s vision, the constant focus of the divine council is on giving glory, honor, and worship to the one who sits upon the throne. The place of worship, and the shape of worship, are then earthly icons of the divine assembly into which human persons enter in worship. The tabernacle’s curtains and veils were decorated with images of angelic beings in worship, culminating in the cherubim atop the ark of the covenant in the most holy place. Likewise in the worship itself, as maintained in the Orthodox Divine Liturgy, there is a conscious awareness and invocation of the fact that worship is a participation in the continual and eternal worship enacted by the divine council in heaven.

In a handful of cases, human persons were actually made members of the divine council either without experiencing physical death, or shortly thereafter as their bodies were taken up. The first of these is Enoch, listed seventh from Adam in the genealogies of Genesis 5:21. The exact nature of what happened is not described in Genesis in detail, which states only that, ‘Enoch walked with God and he was not for God took him’ (v. 24). Sirach says little more, only that ‘Enoch pleased the Lord and was taken up into heaven. He became an inspiration for repentance for all time to come’ (44:16). For Sirach, Enoch is a model of salvation from a sinful world on its way to judgment through a life of righteousness and repentance. Likewise the book of Wisdom understands Enoch to have been taken out of a world full of wickedness before it could corrupt his innocence (4:10-15). Beyond these brief mentions in scripture, however, a vast body of tradition related to the person of Enoch exists in Second Temple Jewish literature. The most well known of these texts is 1 Enoch, though there is a great body of other material, and 1 Enoch itself consists of multiple collections of material brought together into one text. This 1 Enoch material is referenced in the New Testament, minimally in 1 and 2 Peter and Jude, and its basic truth was accepted and referenced by the Fathers universally until the beginning of the 5th century, and quite often even after. In 1 Enoch, Enoch is brought into the divine council and receives a vision of the history of the world and the nature of the cosmos, culminating in him receiving a special place within God’s divine council.

Our understanding of this, and similar events to be discussed in the Old Testament is often obscured by modern pop Christian eschatology in which human persons who die either ‘go up to heaven’ or ‘go down to hell’. This is not, of course, the teaching of the scriptures, which teach bodily resurrection in the world to come following the judgment of the living and the dead. Particularly in the Old Testament, there is no distinction made regarding the fate of individuals who die. Both the righteous and the wicked go to the grave, Sheol in Hebrew or Hades in Greek. Both the patriarchs Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and a wicked king like Omri, are said by the Old Testament, at their death, to ‘rest with their fathers’. This is a situation which will be fundamentally transformed at the resurrection of Christ, and that transformation forms the basis of many of the hymns of Pascha.

It is therefore a misunderstanding to interpret what happened to Enoch as ‘going to heaven without dying’, because those who died in the Old Covenant were not seen to ‘go to heaven’ at all. Enoch, rather, is chosen by God to join the divine council as, then, is the Prophet Elijah. In a previous post, Ezekiel’s vision of God’s throne as a throne-chariot was discussed. God’s throne serves as a chariot because his reign is not limited to one particular location, but ranges throughout the creation. This is likewise true of the divine council, for wherever the Lord is, there are the angelic hosts surrounding his throne and serving him. And so, when Daniel describes his vision of the divine council, he sees thrones, plural, set, and then the Ancient of Days takes his throne, while the council surrounds him on lesser thrones (Dan 7:9). That St. Elias is taken to heaven in a fiery chariot is therefore a way of describing that he has been made a member of the divine council alongside the angelic beings. It therefore became a commonplace of Second Temple Jewish literature that Enoch and Elijah would someday return with an angelic mission related to the coming of the Messiah. Likewise, this is why the iconography of St. John the Forerunner combines both the imagery of the returning Elijah, as referenced in the Gospels (Matt 11:13-14, 17:12-13, Mark 9:13, Luke 1:11-17), and angelic imagery. When he and Moses appear on Mt. Tabor with Christ, they are engaged with him in discussion, as councilors to the king.

The final major figure of the Old Testament is Moses. Unlike Enoch and Elijah, the Prophet Moses experienced physical death, as described in Deuteronomy 34:5, but it is then stated that the God of Israel himself buried the body so that no one knew where it was to the day of the writing of the account (v.6). Though not described in the Old Testament, traditions within early Judaism described the fate of Moses’ body and why it was not found. As mentioned in last week’s post, a portion of the curse placed upon the serpent in Genesis 3 was his consignment to the realm of the dead. This took the poetic form of his consignment to eating dust and ashes of the earth, to which the dead would return (Gen 3:14). The scriptures do not teach that the human soul is the ‘real’ person, while the body is a husk which contains it. Rather, they teach that a human person is a union of body and soul, and that the separation of the two at death is unnatural. This is why, for example, they speak of both soul and body being thrown into Hades (Matt 10:28). Because of human sin and rebelliousness, the devil is able to stake a claim to the dead. Because Moses had lived a life which pleased God, and had repented of his sin, His body was not subject to the devil’s claim, and as we are told in Jude 1:9, the Archangel Michael came and contested Satan’s claim to Moses’ body. This story is told in a more full form in Second Temple Jewish literature such as the Assumption of Moses. This understanding of the human body forms the basis for St. John Chrysostom’s Paschal Oration, that the devil and Hades ‘seized a body’ but encountered God, and were embittered. This also forms the basis for the church’s understanding of the disappearance of the body of the Theotokos after her burial, as celebrated at the feast of her Dormition.

Next week’s post will discuss the transformation of the divine

council and humanity’s place in it accomplished through the incarnation,

resurrection, and ascension of Christ.

The Saints in Glory - The Whole Counsel Blog

The

word which we commonly read in English translation as ‘saint’ or

‘saints’, derived from the Latin ‘sanctus’, translates the Greek word

‘agios’ (plural ‘agiois’) which is seen constantly in the inscriptions

of iconography. In the New Testament, this word is used to describe

both the worshipping community of the church in its sojourn on earth and

the ‘dead in Christ’ (cf. Acts 9:13, 32, 41, Rom 1:7, 12:13, 1 Cor 14:33, 2 Cor 9:12, Eph 2:19).

This Greek term is actually the substantive form of the adjective

‘holy’, and could simply be translated ‘holy one’ or ‘holy ones’. The

reason it has traditionally been translated as ‘saints’ is to indicate

that by the time of the New Testament, the term saint was already a

specific term which had a specific usage in the Hebrew scriptures, the

Greek translation of the Septuagint, and in the religious literature of

Second Temple Judaism. The usage of this term as a reference to

Christians in the New Testament serves as an indicator of a change in

the cosmic state of affairs, the fulfillment of Old Testament

prophecies, and the destiny of humanity transformed in union with

Christ.

The

word which we commonly read in English translation as ‘saint’ or

‘saints’, derived from the Latin ‘sanctus’, translates the Greek word

‘agios’ (plural ‘agiois’) which is seen constantly in the inscriptions

of iconography. In the New Testament, this word is used to describe

both the worshipping community of the church in its sojourn on earth and

the ‘dead in Christ’ (cf. Acts 9:13, 32, 41, Rom 1:7, 12:13, 1 Cor 14:33, 2 Cor 9:12, Eph 2:19).

This Greek term is actually the substantive form of the adjective

‘holy’, and could simply be translated ‘holy one’ or ‘holy ones’. The

reason it has traditionally been translated as ‘saints’ is to indicate

that by the time of the New Testament, the term saint was already a

specific term which had a specific usage in the Hebrew scriptures, the

Greek translation of the Septuagint, and in the religious literature of

Second Temple Judaism. The usage of this term as a reference to

Christians in the New Testament serves as an indicator of a change in

the cosmic state of affairs, the fulfillment of Old Testament

prophecies, and the destiny of humanity transformed in union with

Christ.

In the Old Testament, the ‘holy ones’ of God are, first and foremost, the angelic beings who make up the divine council, as seen, for example, in Psalm 89:5-7, “Let the heavens praise your wonders, O Yahweh, your faithfulness in the assembly of the holy ones. For who in the heavens can be compared to Yahweh? Who among the sons of God is like Yahweh? A God greatly to be feared in the council of the holy ones, and awesome above all who are around him.” The angelic beings of the divine council surround the Lord, and while some of them fell and came to be worshipped as gods by the nations, none of them is like the only true God, Yahweh the God of Israel. “Who is like you among the gods, oh Yahweh? Who is like you in majesty among the holy ones?” (Ex 15:11 LXX). Israel, when gathered in worship participates in the divine council, and so they too, in these moments, are described as ‘holy ones’ (cf. Lev. 11:44-45, 19:2, 20:7, 26, 21:6; Num 15:40, 16:3). When the Lord is depicted as coming in judgment, it is with his holy ones, as in Zechariah 14:3, “Then the Lord my God will come, and all the holy ones with him.” This stands in parallel to New Testament passages such as Matthew 16:27. In describing the coming of Yahweh to Israel, Moses says, “The Lord came from Sinai and dawned from Seir upon us. He shone forth from Mount Paran. He came from the ten thousands of holy ones with flaming fire at his right hand. Yes, he loved his people. All his holy ones were in his hand” (Deut 33:2-3). The holy ones of God are here depicted as ‘flaming fire’, an image which is also used in Psalm 104:4, “He makes his angels spirits, his ministers flaming fire”, as quoted in Hebrews 1:7.

The understanding of this imagery in Hebrews is important, and is elaborated in other terms by St. Dionysius the Areopagite in his Celestial Hierarchies. The fire in which the angelic hosts share, to varying degrees in their orders, are the divine energies, the grace and glory of God. Hebrews 1 uses this as a comparative to Christ. While the angels graciously partake of the glory of God, that glory belongs to Christ himself as God (Heb 1:8-12). In Hebrews 2, however, the argument continues to describe the incarnation of Christ, who was ‘made for a little while lower than the angels’ but then ‘crowned with glory and honor’, after which all things are made subject to him (2:7-8). While we do not yet see all things subject to Christ, we see Christ who was incarnate so that he might taste death for all mankind now crowned with honor and glory (v. 8-9). This discussion in Hebrews has an important frame. It begins with the statement that, “it was not to angels that God subjected the world to come” (2:5). This stands in contrast to the previous age of the old covenant, in which the nations had been given over to angelic dominion. Importantly, however, Hebrews is not merely pointing to Christ’s reign over all creation, but also to those who are saved through him. Those who find salvation in Christ are here called his sons (2:10, 13), parallel to the sons of God of the old covenant. They are called his brothers (v. 11, 12), concerning whom he testifies in the congregation. Through the incarnation, Christ has delivered those who share in his human nature from death and the devil (v. 14), and through the ascension, he has elevated that nature even above the angelic nature. In Christ, human persons become partakers of the divine nature beyond any of the ranks of angels, and come to be rightly numbered among the holy ones.

In the Old Testament, God’s authority on earth was imaged and represented by human authority within Israel. Moses, the judges from Joshua through Samuel, and the king represented the rule of God over his people. The 70 elders in Israel equaled in number the angelic beings of the divine council who had been assigned rule over the nations. The Davidic line, of God’s chosen king over Judah, in particular was a representation of God’s authority on earth, its court representative of the divine council. David and his line, however, represented the rule of God prophetically, such that the fulfillment of God’s reign over his people was ultimately seen to be the Christ, the Messiah, who would actualize God’s rule over his people in the age to come. It is for this reason that the prophecy of 2 Samuel 7:16, that David’s house and kingdom will be forever, is transformed in view of the coming Messiah in 1 Chronicles 17:14 to the promise that David’s descendant will live in God’s house, and God’s kingdom will be forever. These prophetic themes are fulfilled in the person of Jesus Christ, such that before his ascension into heaven to be re-enthroned, he states, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Therefore go and make disciples of all nations…” (Matt 28:18-19). God’s rule over Israel has found its fulfillment in Jesus as the Christ, and Christ has also reclaimed authority over all the nations through the defeat of the fallen spiritual powers who had controlled them (Col 2:15).

The New Testament is clear that this authority is no more isolated in the new covenant than it was in the old. Quite the opposite. Now, through Christ, human persons have entered into glory and joined the divine council as part of the family of God. The promises of the scriptures regarding Christ’s saints are not merely promises of passive rest, but promises of participation in the rule and reign of Christ. Christ tells his disciples that when all is made new and he sits upon his throne after the ascension, they will ‘sit on twelve thrones judging the twelve tribes of Israel’ (Matt 19:28). St. Paul says that the saints will judge the world (1 Cor 6:2) and in the next verse, that the saints will judge even angels (v. 3). He says that we are already seated with Christ in the heavenly places through Christ’s ascension (Eph 2:6). The Revelation of St. John describes the present age, before Christ’s glorious appearing, during which Christ reigns in the midst of his enemies, as the time during which the saints are raised to rule and reign with Christ in the heavens (Rev 20:4-5). Revelation then goes on to describe the role of the saints in glory as that of priests (v. 6), who make intercession before the throne of Christ.

The saints in glory, therefore, are not only filling the place in the

divine council formerly occupied by the angels that fell, but also the

role. It is in light of the fact that these members of the divine

council were called ‘gods’ and ‘sons of the Most High’ (Ps 82:6) that

the New Testament authors speak of our becoming sons of God, and the

Fathers, as famously St. Athanasius, speak of men becoming ‘gods’. It

is for this reason that since the very beginning of the Church, nations,

cities, churches, families, and individual persons which once had

‘gods’ allotted to them have instead found heavenly patrons in the

saints. This is not, as some would suggest, some sort of concession to

popular polytheism. Quite the opposite. Rather, it is a function of

the gospel of Jesus Christ, which declares that the malign demonic

powers who once enslaved the nations have now been cast down (Gal 4:8-9,

Col 2:8, 20), and that the saints now rule and reign with Christ,

judging the nations as he promised. Just as in the old covenant

believers sought the intercession of the holy ones before the Lord (cf.

Job 5:1), so also, as the saints in glory serve as priests before the

throne of Christ, they make prayerful intercession for the faithful (Rev

20:6). Just as the ranks of angels had different roles and

participated differently in the grace and glory of God, so also the

saints have their unique roles (1 Cor 15:40-41). The royal priesthood

of the saints in glory is part and parcel of, and inseparable from, the

authentic gospel of Jesus Christ.

Queen and Mother - The Whole Counsel Blog

Recent

posts have discussed the divine council of angelic beings which

surround the throne of God, the way in which certain individuals in the

Old Testament were exalted to join that council, and the way the saints

in Christ become members of the divine council, sharing by grace in

Christ’s rule over his whole creation. Within these themes, and the

mediatory role of the saints and their patronage, the Theotokos, Mary,

the Mother of Jesus Christ, has a special role, as has been recognized

within the Christian faith from the very beginning. The veneration of

the Theotokos in the West developed in ways which ultimately produced

Marian dogmas which the Orthodox Church does not recognize. In response

to these developments, the heirs of the Protestant Reformers, though

not those Reformers themselves, reacted by seeking to minimize the

importance of the Theotokos, to the point of rejecting details of her

personal history and life which had been held universally since our

earliest sources. Once the role of the Theotokos within the divine

economy had been repudiated, Protestant scholars had the need to explain

how these teaching came into being, and came to be universally held.

It has become common for those scholars to suggest some connection

between the veneration of St. Mary and pagan goddess worship, related to

their suggestion that the veneration of the saints in general contained

some connection to polytheism. As was seen

in the case of the role of the saints, however, it will be seen that

the veneration of the Theotokos as experienced within the church has

existed from the beginnings of the faith, being grounded firmly in the

scriptures and in the religion of Second Temple Judaism and its

anticipation regarding the mother of the Messiah.

Recent

posts have discussed the divine council of angelic beings which

surround the throne of God, the way in which certain individuals in the

Old Testament were exalted to join that council, and the way the saints

in Christ become members of the divine council, sharing by grace in

Christ’s rule over his whole creation. Within these themes, and the

mediatory role of the saints and their patronage, the Theotokos, Mary,

the Mother of Jesus Christ, has a special role, as has been recognized

within the Christian faith from the very beginning. The veneration of

the Theotokos in the West developed in ways which ultimately produced

Marian dogmas which the Orthodox Church does not recognize. In response

to these developments, the heirs of the Protestant Reformers, though

not those Reformers themselves, reacted by seeking to minimize the

importance of the Theotokos, to the point of rejecting details of her

personal history and life which had been held universally since our

earliest sources. Once the role of the Theotokos within the divine

economy had been repudiated, Protestant scholars had the need to explain

how these teaching came into being, and came to be universally held.

It has become common for those scholars to suggest some connection

between the veneration of St. Mary and pagan goddess worship, related to

their suggestion that the veneration of the saints in general contained

some connection to polytheism. As was seen

in the case of the role of the saints, however, it will be seen that

the veneration of the Theotokos as experienced within the church has

existed from the beginnings of the faith, being grounded firmly in the

scriptures and in the religion of Second Temple Judaism and its

anticipation regarding the mother of the Messiah.

The earthly authorities of the old covenant were a direct reflection of the divine council, through which the God of Israel exercised his rulership and authority over his creation. The earliest institution of the Torah were the 70 elders surrounding the one appointed to judge Israel, 70 in number because that was the number of the divine council assigned to govern the nations (Deut 32:8). This remained when there came to be a divinely-appointed king. The earliest kings, Saul and David, as they made war to secure the land given them by God, were surrounded by their mighty men (gebur’im) who led their armies, in parallel to the heavenly hosts surrounding YHWH Sabaoth. The Archangel Gabriel’s name identifies him as the ‘Gebur’ or mighty man of God. With the kingdom established under David, this took the form of the elders of the people and the royal court surrounding David as he ruled and administered that kingdom. In all of these cases, the earthly authority served as an image of God’s heavenly authority, and was commanded to serve in the administration of God’s authority. Kings are then judged based on how well they image the righteous rule of God on earth in their role. The king and his royal council was not only an image and earthly reflection of God’s heavenly rule, but was also a prophecy of a day when earthly and heavenly rule would be united as one in the Messiah.

Within the southern kingdom of Judah, which was ruled by the line and house of David from the division of the kingdoms until the exile in Babylon, an important institution grew up within the king’s court. It is this Davidic line which 1 and 2 Chronicles go to great pains to emphasize continues after the destruction of Judah, such that it will one day produces the Messianic king. This is why we are reminded in the genealogies of St. Matthew and St. Luke, and the accounts of Jesus’ birth that he is of this line according to the flesh. Typically, when we consider the king and queen of a nation, based on medieval Europe we assume that the queen of a nation is the wife of the king. This, however, is because that medieval paradigm had been deeply effected by Christianity such that it had to at least make pretense to monogamy. In the ancient world, as we see reflected in 1 and 2 Kings and 1 and 2 Chronicles polygamy was widely practiced by the wealthy, which of course included kings. This was never a way of life sanctioned by God, in fact, the Torah explicitly forbids kings from practicing polygamy (Deut 17:17). It was, however, the reality. For this reason, rather than the office of queen belonging to a first or favored wife, it belonged to the mother of the king. Kings might have many wives, but could have only one mother. The reality of polygamy, however, does not fully explain the institution of queen mother within Judah because there is no parallel institution in the northern kingdom of Israel, let alone in many other monarchies of the ancient world which were equally polygamous. It is unique to David’s line within Judah.

The origination of this institution is describes in 1 Kings 2:19, as Solomon shortly after his succession to the throne has a second throne brought out and placed on his right hand for his mother, Bathsheba, to sit beside him as queen. The significance of being at the right hand of the king is clear throughout the scriptures, preeminently in Christ’s own enthronement being described as being at the right hand of the Father. This is the preeminent position within the king’s council, and establishes her as his foremost advisor. From this point on, throughout 1 and 2 Kings and 1 and 2 Chronicles, as the succession of each descendant of David to the throne is announced, his mother is named because she holds this role (See 1 Kgs 14:21, 15:2, 15:10, 22:42, 2 Kgs 8:26, 12:1, 14:2, 15:2, 15:13, 15:30, 15:33, 18:2, 21:1, 21:19, 22:1, 23:31, 23:36, 24:8, 24:18 and parallel passages in 1 and 2 Chronicles). In a particularly dark period of Judah’s history, Athaliah used the authority of this role as queen mother to attempt to wipe out the Davidic line (2 Kgs 8:26, 11:1-20). This institution is referred to elsewhere in the Old Testament, a chief example being Psalm 45. This Psalm is an ode to the king, and as the king is the icon of the God of Israel, it moves easily from praise of the king himself (v. 2) to praise of God (v. 6), with the lines sometimes blurring between the two. This, too, is prophetic of the Messianic king who will someday unite the two. Within the imagery of this ode to divine kingship is the statement that at the king’s right is the queen in glorious array (v. 9). This Psalm concludes with a prophecy of the future role of the saints in governing the nations (v. 16).

The most basic claim of the entire New Testament is that Jesus is the Christ, the Messiah. Because Christ is also proclaimed to be the incarnate second hypostasis of the Holy Trinity, in him heaven and earth, the divine and the human, are united. This includes, at his enthronement at the ascension, the union of the throne of God and the throne of David, already, as we have seen, prophetically linked in their institution. The reign of Jesus Christ over his kingdom is not only the bringing together of Davidic and divine rule, but is the fulfillment of the former. The words of Psalm 2:7, “Today you are my son, today I have begotten you” are a critical part of this royal psalm, read at the succession to the throne of a new Davidic king. Within the idea of adopted sonship is the idea that the son now has the obligation to serve as an image of the Father. This is fulfilled in Jesus Christ, who is the express image of God the Father (Heb 1:3). But it is also fulfilled at the baptism of Christ, in which Christ is anointed at the hand of the prophet, not with oil but with the Holy Spirit, and the words of succession are spoken (Luke 3:22, Acts 13:33, Heb 5:5). Christ is the true Son of God, begotten, not adopted.

For a faithful believer in the God of Israel in the first century AD, religious expectation was focused in the coming of the Messiah, and the beginning of the Messianic age. It would, therefore, have been natural when such a person heard the apostolic proclamation that Jesus of Nazareth is the Christ who has come, to ask the name of his mother. It would have been a natural expectation, based in the scriptures and traditions of the Jewish people, to expect that his mother would have this role, at his right hand, as closest advisor and queen. The New Testament authors take great pains to correct popular misunderstandings related to the Messiah, particularly the idea that he would be a political leader in this world, and would come to establish an Israel in this world free from Roman domination. At no point, however, do these authors seek to correct this expectation as it pertains to Christ’s mother. Repeatedly, throughout the scriptures of the New Testament, these expectations are reinforced through the importance of the Theotokos not only in the ministry of Christ, but in the early community of the church as described in the opening chapters of the Acts of the Apostles. As just one example, there is a clear parallel between the interaction between Bathsheba and Solomon in 1 Kings 2, and that between the Theotokos and Christ at the wedding at Cana (John 2), though the Theotokos shows herself a wiser and more holy woman than her ancient ancestor.

It is this understanding which has led, since the beginning of the Christian faith, to the special role given to the Theotokos among the saints in glory. It is she who stands at the right hand of Christ the king, and among the intercessors with whom Christ shares his rule and reign, she has a special status of honor. She stands as the fulfillment not only of queen motherhood, but of motherhood itself (Gen 3:15), and even, we may see, of womanhood.

Comments

Post a Comment